Hazel, 2015

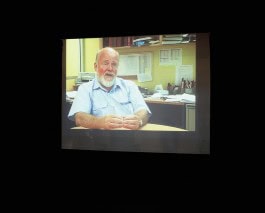

Three channel audio video installation, 9:48 minutes (2016)

Single screen HD video, 8 minutes.

Premiere screening at the International Myotonic Dystrophy Consortium Meeting, Paris. (2015)

Hazel:

Resemblance is a complicated thing. My entire first year at The Glasgow School of Art I was asked if I had a sister in second year. I was used to having a very-alike-could-be-twin-sister, but she wasn’t at art school, didn’t even live in the same city. Who was this other woman? When we eventually met, awkwardly, at the bar in the student union (of course) we both stood off; what was in me that they saw in her? Freckles, a long nose, blue eyes… In her friendly but quizzical look I saw her think the same. More than 20 years later we still occasionally meet around town and I wonder if others think we look alike even now, or has age affected our similarity?

I wonder too if I still look like my sister? This is an ongoing puzzle that has coloured my many years of research and collaboration with scientists. When do you stop looking like your family and start looking like the symptoms described in a textbook? When is familial resemblance overtaken by another layer of inheritance that, like long legs or short tempers, also comes from your parents? An inheritance that can cause all sorts of assumptions about health, ability and competence to be made both by ‘the outside world’ and within family dynamics.

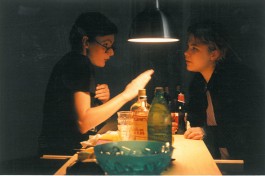

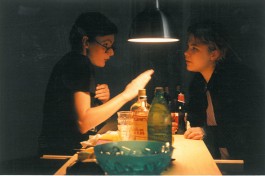

The interviews for the artwork Hazel published here recognise the importance of considering the private, domestic experience of an inherited genetic condition by asking women to speak frankly about their own lives; I selected a very specific group for interview – sisters between the ages of 30 and 70, where one (or two) have inherited the myotonic dystrophy gene and one has not. This was to mirror my own position as an unaffected sister, but also to address the visibility of progressive female ageing, both in general and within the specific world of genetic research and care. I have used these women, sisters, to portray a broad range of female experience connected by a single genetic factor, to illuminate the loss that affects each of us differently. There are certain shared aspects that directly connect to appearance – whether that be facial deterioration or the consideration of when, if at all, an affected sister becomes more recognised for her disability than her familial characteristics – but there is also much that still connects to individual life experience.

The women in the Hazel research are not poster girls for disability, nor even for their own genetic condition. They are quietly spoken women living with slow physical deterioration that’s not just marked by wheelchairs or walking sticks, but by hair loss, collapsed facial muscles and low income employment. But they are also daughters, friends, wives and mothers. They wear makeup, have tattoos, take holidays, cook dinner. Some are employed, some are not. Even when discussing highly emotional situations, such as infertility or the loss of a child, there is calm and there is resilience. Room for Hazel, and this research, to extend beyond a simple retelling of physical decline or collection of medical data into an opportunity to consider everyday activity, family relationships. To think of similarity, and what makes us look and act the same, and what divides and separates us beyond symptomatic observation.

In the film, two faces appear side by side. When a woman is seen alongside someone of a similar physical and genetic background who is also beginning to deal with the ageing process but does not have myotonic dystrophy, in a society filled with mediated images of what a woman in her 40s, 50s and 60s should look like, is the experience portrayed here useful to illuminate a loss that is difficult to define? Medicine references the moment a wheelchair arrives in the house (whether used or not) as a milestone in the condition, and the biographical disruption that causes young women to use walking sticks before their mothers, or grandparents to raise a toddler when their daughter is unable to. It doesn’t always consider the lives lived beyond the clinic, and the personalities of those involved.

Collaborative process and the coalition of expert knowledge are essential tools for advancing research across many fields. Communication and observation are a cornerstone of the art-making process I was trained in, a process that at times overlaps in approach with other disciplines from genetics to social sciences. A refrain of anthropologist James Clifford’s is his encouragement of anthropology’s scientists to reflect on their relationship to the people/cultures they are studying. For example, he asks: ‘What if someone studied the culture of computer hackers […] and in the process never “interfaced” in the flesh with a single hacker. Would the months, even years, spent on the Net be fieldwork?’ Regardless of the answer to the question posed, it is hardly a stretch to see how this reflection on observer/participant methods can be transposed to the context of scientific/medical research and artistic practice: must researchers engage with the subjects of their inquiry? How do they do that? What are the advantages/limits of detached observation? What are the advantage/limits of personalised approaches? What insights would a collaborative approach that enables experts in different fields to come together somewhere between these two approaches provide?

These are points that the myotonic dystrophy community has considered through the structure of conferences and meetings in the past decade that have raised and acknowledged the expertise that families hold in the field. Patients are experts too, and art can be a powerful method of articulating lived experience. Everyone has a story to tell, to share, and it’s on that basis that this book is published.

One point raised in the interviews is ‘What if my sister didn’t have it?’ something that, alongside a consideration of familial resemblance – of when siblings might start to look like their condition and not their sister – hangs like a cloud. Two women mulling over a what-if scenario that is difficult to voice. Is it OK to wish your family didn’t have this? What would life be like with ordinary genes? Interestingly all the women here were diagnosed as adults; in childhood no genetic condition was known. But there were often differences: health problems, tiredness, an undefined lack of something; and in education and later employment. These are contemplations that have no answer in medicine or clinical fact and are not confined to myotonic dystrophy. Perhaps everyone with a sister wonders what it would be like to have a different sister, and those with no sisters wonder what it would be like to have one at all.

I don't think it's possible to answer the question if I feel I've lost something because I don't know what it would be that I've lost. … if you feel you've lost the sister that you would have had, if you had had her, you've then lost the sister that you do have.

Jacqueline Donachie

Extract from Deep in the Heart of Your Brain: notes from an exhibition, Pg 7-9.

Softback, 206pp. Published by Glasgow Museums 2017

Notes: There is no scientific evidence of a difference in the manifestation of the condition in men and in women other than in terms of fertility and reproduction, and working with sisters only, as opposed to male siblings, stems from my personal situation.

James Clifford, Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997; 61

STEP 2021

Beautiful Sunday 2021

Right Here Among Them 2017

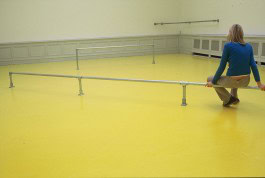

Pose Work For Sisters 2016

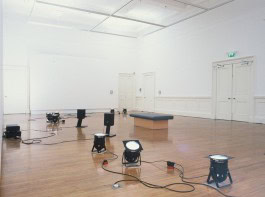

Deep in the Heart of Your Brain 2016

South (Oslo) 2015

Hazel 2015

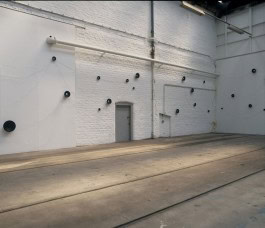

Keep Up 2014

Glasgow Slow Down 2014

New Weather Coming 2014

Mary and Elizabeth 2014

Melbourne Slow Down 2013

Glimmer 2013 & Ongoing

Patricia Fleming Projects 2013

The Sunniest Person I Know 2012

Temple of Jackie 2011

Speedwork 2010

South (Highland) 2009

Huntly Slow Down 2008

Weight 2008

Tomorrow Belongs to Me 2006

Green Place 2004

Games 2003

A Walk for Grenville Verney 2003

Dear Wives 2002

The House of Fun 2002

Three Pinkston Drive 2002

South 2001

Edinburgh Society 2001

DM 2001

In the Arms of Strangers 2000

The Trees, The Book and The Disc 1999

Holy Ghost 1999

Sword 1999

The Hoping Room 1997

Live Breaks 1997

Advice Bars 1995-2001

Part Edit 1994

© Jacqueline Donachie 2025

STEP 2021

Beautiful Sunday 2021

Right Here Among Them 2017

Pose Work For Sisters 2016

Deep in the Heart of Your Brain 2016

South (Oslo) 2015

Hazel 2015

Keep Up 2014

Glasgow Slow Down 2014

New Weather Coming 2014

Mary and Elizabeth 2014

Melbourne Slow Down 2013

Glimmer 2013 & Ongoing

Patricia Fleming Projects 2013

The Sunniest Person I Know 2012

Temple of Jackie 2011

Speedwork 2010

South (Highland) 2009

Huntly Slow Down 2008

Weight 2008

Tomorrow Belongs to Me 2006

Green Place 2004

Games 2003

A Walk for Grenville Verney 2003

Dear Wives 2002

The House of Fun 2002

Three Pinkston Drive 2002

South 2001

Edinburgh Society 2001

DM 2001

In the Arms of Strangers 2000

The Trees, The Book and The Disc 1999

Holy Ghost 1999

Sword 1999

The Hoping Room 1997

Live Breaks 1997

Advice Bars 1995-2001

Part Edit 1994

© Jacqueline Donachie 2025